February 8, 2007, was a major milestone in the ongoing campaign by workers and their unions for justice for asbestos victims. On that day, the notorious James Hardie company agreed to a compensation deal for its former employees who were the victims of asbestos.

This agreement was the direct result of the heroic and inspiring campaign by victims of asbestos and the union movement for justice.

James Hardie was once one of the biggest companies in Australia. It had a long and dirty history with asbestos though mining, producing fibro sheets and pipes, insulation, and brake linings.

As the ACTU noted in 2007, evidence that was presented at the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry, known as the Jackson Inquiry, suggested that James Hardie had knowledge of some of the dangers of asbestos as early as the 1930s.

James Hardie is probably the most famous example of a compensation fight against big business for exposing its workers to asbestos. But it is far from the only one.

The fight against asbestos and for justice for asbestos victims is one of deep emotion and commitment for the union movement. It is about our rights as workers to be safe at work, and to enjoy long, decent, healthy lives.

These rights were ruthlessly stripped from the many workers who were exposed to asbestos by companies that were aware of its harmful effects.

Former ACTU Secretary Greg Combet was prominent in the campaigns for justice for victims of asbestos. He wrote in his memoir:

‘Clinical accounts, epidemiological studies and actuarial models do not disclose the emotional impact of asbestos-related diseases. Until you spend time with the victims, you don’t appreciate the human side of the asbestos epidemic. They have a gnawing feeling of injustice. They struggle to find any reconciliation or understanding. Other serious illnesses are always a human tragedy, but the cause may be attributed to genetic predisposition, unhealthy lifestyle, unavoidable accidents, or the luck of the draw. But for those with asbestos-related diseases, their condition is not due to the workings of chance. They are sick because they were exposed to a substance known by its manufacturers to be deadly. They take the knowledge of this injustice, the anger and the despair, to the deathbed.’

Despite asbestosis being first identified in the 1920s, and the link between asbestos and lung cancer being recognised by medical experts in the 1930s, warnings were not placed on asbestos products until the 1970s, and James Hardie manufactured asbestos products into the 1980s.

Union actions against the use of asbestos, and then for compensation, began in the 1970s, when unions took industrial action against the use of asbestos. Major compensation cases began to be launched in the 1980s.

James Hardie became the focal point of the campaign for compensation. Two major developments in 2001 gave additional impetus to this campaigning.

In that year, James Hardie Industry Ltd. sought to legally separate itself from subsidiaries that had asbestos liabilities. It moved to create a new company that would hold the liabilities and would be formally separated from the main James Hardie Industry Ltd. This new company was called the Medical Research and Compensation Foundation Ltd. and its complete assets, valued at $293million, were well below what would be required to pay appropriate compensation for the growing number of recognised victims.

That same year, the James Hardie parent company’s board of directors authorised a corporate restructuring, and planned a move to the Netherlands, leaving little more than a shell company behind.

The full implications of this were not immediately clear. But in late 2003, the Medical Research and Compensation Foundation Ltd announced a major anticipated shortfall in funds that would be needed to pay compensation liabilities that were owed to workers afflicted by asbestos’s effects.

There was a serious risk that the Foundation would soon run out of money, and the highly-technical legal manoeuvrings that the James Hardie parent company had engaged in would protect it from needing to pay the compensation owed.

As Greg Combet later recalled:

‘It struck me that the only chance of securing justice was to apply a fearsome blowtorch of public anger to the directors of the company—to foment community outrage and use political influence to force James Hardie to do the right thing.’

A major campaign led by the union movement and former James Hardie workers was launched.

One of the most influential figures, and passionate spokespeople, in this campaign was the legendary Bernie Banton.

Bernie Banton suffered from asbestosis after having worked for a James Hardie subsidiary handling asbestos between 1968 and 1974. He was a powerful campaigner representing victims of asbestos, the Vice President of the Asbestos Diseases Foundation, and a member of the AMWU.

Bernie once told the ABC: ‘I’ve said right from the beginning of this fight that until they put me in a box, I’ll be out there fighting’.

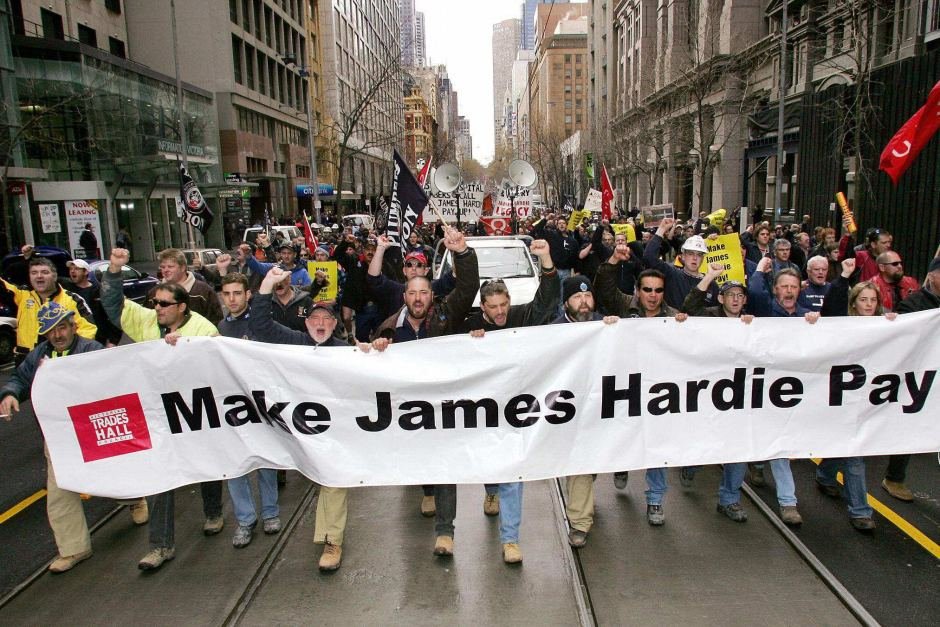

In 2004, serious mobilisations sought to put pressure on the James Hardie parent company. A number of unions, such as the AMWU and CFMEU, played a leading role in these mobilisations and in building public pressure. This included a rally of tens-of-thousands of unionists rallying to ‘Make James Hardie Pay.’ Construction unions announced a ban of James Hardie products on worksites.

As Greg Combet related: ‘We had nothing going for us except our capacity to communicate this injustice to the community.’

The union-led campaign organised public rallies, actions outside the James Hardie offices, called for a boycott, and arranged for questions to be asked at shareholders meetings.

In the United States, where James Hardie did most of its business, unions rallied in solidarity with the campaign at the company’s California HQ.

Even though it seemed that the James Hardie parent company was in the more powerful position, it was clear that public opinion was overwhelmingly on the side of the asbestos sufferers fighting for justice.

Public pressure and action by the NSW Government led to James Hardie negotiating for compensation. The ACTU’s Greg Combet and Bernie Banton both played leading roles in these negotiations. Combet said of Banton: ‘Bernie has been there every day and has lent to this entire process a decency and humanity that was sorely needed.’

Eventually, after much intensive negotiation, an agreement was reached for redress, and a new compensation fund formed, with James Hardie providing an initial funding of $184.3million and pledging to continue to contribute to the fund out of its operating cashflow each year to keep up with liabilities based on the latest data on compensation claims.

This deal was formalised and agreed to by James Hardie’s shareholders on 8 February, 2007.

The deal committed 35% of the company’s operating cashflow each year, for the next forty years, to victims of asbestos.

In 2007, after Joe Hockey had said that the unions were dying, an indignant Banton shot back that without the unions former James Hardie workers would have gotten ‘diddly-squat’ in compensation.

Watch Bernie Banton and Greg Combet speak about the campaign at a union rally in November 2006.

Bernie Banton died from mesothelioma on November 27, 2007. He was 61 years old.

Greg Combet said in tribute: ‘Bernie had a rare capacity, a capacity to connect with people and to inspire in them the same passion for justice that he himself felt and he moved the Australian community.’

In 2010 the Gillard government announced the establishment of the National Asbestos Management review, charged with plans for asbestos awareness and removal.

In 2012, the High Court found former James Hardie directors had misled the stock exchange about the compensation fund – a ruling that made clear the company had been misleading the public about compensation to victims.

Since the 2007 agreement, there has been controversy over the amount of payment into the compensation fund (at the same time as it made large dividend payments to shareholders).

Today, campaigning against asbestos continues, with the Australian union movement strongly contributing to global action to end the use of asbestos. Australia’s unions are also leading a campaign against other workplace substances such as the use of silica dust which can cause lung cancer and other adverse effects.