In 1979 the Union of Christmas Island Workers (UCIW), made up predominantly of migrant workers labouring in colonial conditions, took on the Australian government and the island’s mining giant and won.

This is their story.

Colonial conditions on Christmas Island

Christmas Island was annexed by the British Empire in 1888 and is best known for its phosphate mining. Up until 1958, it was administered from Singapore. In that year, the island became an external Australian territory but it was not brought under the auspices of our laws, including industrial laws.

Life on the island was dominated by the phosphate mine run by the British Phosphate Company (BPC), which was co-owned by the Australian and New Zealand governments. Conditions were positively colonial.

The management and supervisors of the mining operation were predominantly white Australians. The mining workers who conducted the toil were predominantly migrants from Asia, most commonly recruited from Malaysia and Singapore.

There was overt segregation between white supervisors and Asian miners both economically and socially.

White supervisors were paid Australian wages, received Australian benefits, and lived in comfortable amenities. Asian workers lived in terrible accommodation and received wages well below the Australian minimum.

But the migrant workers on Christmas Island did not tolerate being subject to these conditions.

Worker action against racism

The spark that lit the flame came on the 26th of March 1974 when the BPC fired the chief interpreter in its administrative office, the well-liked community figure Teo Boon How, and order him to leave the island within 24 hours.

The next day more than 1,100 workers refused to report to work and marched in protest at Teo’s treatment. The protest stopped Teo from being deported, and forced his reinstatement. It was a significant assertion of collective power and a tangible victory for the workers.

Teo How was integral to the efforts that led to the formation of the Union of Christmas Island Workers (UCIW). Michael Grimes, a local schoolteacher, was elected as the first General Secretary. Lim Sai Meng, a worker with a Chinese background who had come to the Island from Malaysia in 1973, was elected as President.

Building the union was difficult work, calling for a great deal of commitment from activists who would spend all day working, and their evenings addressing the many grievances of their workmates.

But all the hard work paid off. In its first negotiations with BPC the workers, now bargaining collectively, achieved positive increases. In 1976, the UCIW affiliated with the ACTU.

In 1977 the ACTU adopted a policy at its Congress that supported the UCIW’s campaign to extend the protection of Australia’s arbitration system to the island, and labelled conditions there ‘economic apartheid’.

In 1978, the UCIW elected a new General Secretary, Gordon Bennett. Bennett was an English migrant with a more militant style of organising. Under Bennett’s leadership, the UCIW called for a $30 a week raise and minimum wage parity with the rest of Australia. The workers demanded full Australian citizenship rights for all Christmas Island workers.

The strike of 1979

By 1979 the UCIW had built its collective strength. Its members were determined not to put up with the racist mistreatment of BPC any longer.

In March that year, tensions escalated when BPC sacked three workers in the transport pool after a dispute over rostering. A strike broke out on 21 March, in response to which BPC ordered its senior supervisors to undertake driving duties.

This infuriated the workers and led to a strike being immediately called which lasted for two weeks. In early April an agreement was struck by BPC and the UCIW that included a pledge that there would be no victimisation and that negotiation would begin on a new award for the island’s workers.

Negotiations on the UCIW’s log of claims began in May, 1979.

The UCIW argued for a pay increase of $30 per week. In response, BPC offered a pay increase of $4.80. It was a clear insult to the workers.

While negotiations continued, workers increasingly began to complain about the health hazards caused by high dust levels. The UCIW informed BPC that its members had ceased work for health reasons in some parts of the mining operations, but were not on strike.

Through June, more and more stop works over health and safety concerns took place.

BPC stood down 300 ship loaders without pay accusing them of breaking the agreement between the company and the union. The UCIW insisted that its members were not on strike, and that there was no stand down clause in the Award, making BPC’s action illegal.

At the end of the month the Deputy President of the Arbitration Commission, James Taylor, arrived on Christmas Island to host a hearing on the dispute.

In an act interpreted widely as a form of colonial arrogance, he ruled in favour of BPC and inserted a stand-down clause into the ship loader’s agreement that retrospectively authorised BPC’s actions. Workers protested and the UCIW withdrew the offer it had previously of a seat for Taylor on a plane they had chartered for the mainland.

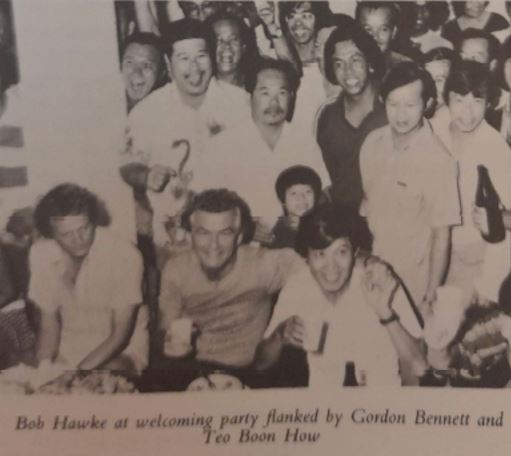

There was no sign of the campaign abating. Bob Hawke, ACTU President, arrived on Christmas Island in July to assist the UCIW and to try and find a way through the impasse.

Hawke met with the BPC General Manager and came to an agreement that would see the 300 ship loaders who were stood down able to return to work with lost wages paid in compensation. Hawke was able to get the company to commit to negotiating the $30 a week claim – but this was just a commitment to negotiate, not an agreement to pay the higher rate the UCIW was campaigning for.

And so the struggle continued.

The Hunger Strike

Six UCIW members took the campaign to the mainland, making a trip to Canberra to negotiate directly with government as well as BPC.

BPC, responding to the substantial pressure the union was generating, offered a pay increase of $19 per week. Following its insistence that any increase above $4.80 would bring financial ruin, this just served to consolidate the UCIW’s attitude that the company was obscuring the reality.

Feeling that progress was being obstructed, the strikers decided to set up a tent protest camp out the front of parliament house.

Supporters from the broader union movement provided them with supplies, but the strikers had to endure the Canberra chill in tents with just sleeping bags and a couple of heaters for warmth.

On the island, workers determined at a mass meeting not to allow phosphate to leave the island until their demands had been properly responded to.

Tired of inaction with the negotiations, the delegation of strikers determined to take more drastic action to speed things along. On the lawns of the parliament house, they launched a hunger strike.

The publicity generated by the hunger strike caused immense embarrassment for BPC and the government.

On 7 August, 1979, BPC tabled an offer of an increase of $30 per week. It turned out, BPC did have the capacity to pay after all.

Victory!

This was an extraordinary victory for the UCIW workers. The Hunger Strikers returned to the island and were welcomed as heroes.

In addition to the pay increase, the UCIW strikers also won rights to permanent residency and a clear pathway to Australian citizenship, a massive achievement.

The union movement proudly remembers the courage and heroism of the UCIW strikers of 1979!