Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this webpage does include the images of deceased persons.

On 1 May 1946, Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara walked off the stations. The strike that began on that day lasted for three years.

The Pilbara Strike was a heroic and inspiring collective action by Aboriginal workers. It is a moment of history every unionist should know about. This is the story of three years of determined struggle by Aboriginal workers against racism and for respect and self-determination.

Background to the strike

The strike was sparked by the constant racist indignities these Aboriginal workers were subject to on the pastoral stations upon which they toiled. The owners of these stations had a colonial mindset and daily denied Aboriginal people control over their own lives.

Aboriginal workers were banned from travelling from the pastoral stations where they worked without their boss’s approval, were subject to a series of other racist personal restrictions, and were paid less than half of the rate paid to non-Indigenous workers – or sometimes, paid only in rations.

This system of inequity perpetuated by the station owners was tightly controlled by the local police, who conceived of their responsibility largely as ‘keeping Aboriginal people under control.’

It was common for Aboriginal workers arrested for minor infractions to be transported wearing heavy chains by the police. The police maintained a regular practice of entering Aboriginal camps at dawn to carry out dog culls – literally shooting dogs in Aboriginal camps with rifles in a blatant act of intimidation.

As was the case across Australia, Aboriginal children were regularly stolen from their families.

Aboriginal workers in the Pilbara sought redress, demanding that they be allowed to choose their own representatives to negotiate with the government and station owners.

In addition, they demanded that some of the pastoral stations worked by Aboriginal labour be handed over to Aboriginal control to enable these communities to undertake self-supporting enterprises.

Organising for action

The strike that was launched on 1 May 1946 was the product of substantial organising efforts. The three more significant figures in these early discussions, though far from the only ones, were Clancy McKenna, Dooley Bin Bin, and Don McLeod.

McKenna was the son of a Nyamal mother and a white pastoralist father. He found work as a truck driver, but McKenna’s pay was still below white workers doing the same work – and below the award rate.

Dooley Bin Bin, also known as Winyirin, was born at the turn of the century in the Great Sandy Desert region. He spent much of his adulthood moving from station to station to work various jobs, and by the 1930s commanded great respect as a lawman. He was well known and well respected in this capacity and for his tendency to talk direct and to be uncowed in the face of white authority.

Another leading figurer of the strike was an ally of the Aboriginal workers who took action, Don McLeod. McLeod became a staunch advocate for Aboriginal rights in the region in the 1940s, at the same time as he joined the Communist Party, and launched a scheme to purchase land that Aboriginal workers could turn into an independent community, without success. The Aboriginal workers charged McLeod with being the go-between of the striking communities and the government.

In the years leading up to 1946, McKenna spent a great deal of time travelling across the Pilbara fermenting the idea of a strike. His activity was noticed by the police who threatened to remove him from the district if her persisted.

After this, Dooley Bin Bin began an extensive tour of the stations across the Pilbara from March 1945 agitating for the strike to come, becoming the predominant strike organiser. It was the beginning of an extensive career as an activist and strike leader.

Coordination across the vast expanse of the Pilbara region was an arduous and complicated feat. To assist with coordination Dooley Bin Bin prepared calendars which he etched onto the back of jam jar labels that were distributed to workers on the stations.

The strike begins!

After extensive organising by Aboriginal workers, the strike was launched on 1 May 1946.

The principal demand of the strikers was to be paid in wages, and for the rate of wages to be set at a universal minimum. But workers adapted the specific demands to the conditions at their stations.

The 1st of May had deep symbolic resonance, coinciding with May Day, the international day of celebration of worker struggle. But it was also a date chosen for practical considerations: it was the start of the mustering and shearing season.

At least 800 Indigenous pastoral workers took action on twelve pastoral stations. Over the course of the struggle, workers from 25 pastoral stations joined the strike. Many of these workers were evicted from the pastoral stations, setting up strike camps nearby.

Daisy Bindi was a Nungamurda woman from Jigalong who worked on one of the stations.

In advance of the strike, Bindi had addressed a large number of meetings to build support for the strike, drawing the close attention to the police who even threatened to remover her from the area.

She had demanded the right to receive wages from her employer before the strike began. She used the money to hire a truck to ferry the strikers around once the strike was launched. Bindi led 86 workers off the Roy Hill Station as part of the strike and played an integral role in spreading the action to other stations.

The start of the shearing season had been chosen to leverage the power that Aboriginal workers had. Some of the employers immediately started offering better (though not equal) wages.

But the primary response from station owners was punitive, and the police were quickly summoned. A significant part of the strike that followed would consist of leaders and participants remaining defiant in the face of police violence and arbitrary arrest and intimidation.

“we’ll fill up their jails:” Heroism in the face of repression

Both Dooley Bin Bin and Clancy McKenna were imprisoned on multiple occasions for their role leading the strike. In fact, McKenna would later recall being imprisoned on the day the strike began. Soon he heard someone moving in the small cell next to him, upon calling out, he discovered it was occupied by none other than Dooley.

At one point, the strike leader Dooley Bin Bin was chained to the grill of a cell awaiting trial for six days. At one point during the strike, police arrested 32 strikers, placing chains around their necks. But the strikers would not be intimidated by this violence and repression, and they would not back down.

In the final stages of the strike, the Aboriginal workers led a coordinated mass civil disobedience action that included provision for mass arrests. ‘Never mind’, Dooley said, ‘we’ll fill up their jails.’ This was a concerted effort to remove one of the main tools of control utilised by white authorities: incarceration.

Don McLeod also attracted close police attention, not the least due to the racist assumption that the Aboriginal workers did not have the initiative to direct such an action themselves, and must be led by some insidious outside force. This was well represented at one of his trials, in which McKenna was brought before the court and asked a series of leading question about what directions McLeod allegedly gave the strikers.

McKenna later recounted his response in which he outlined the motivations for the strike:

‘We want to better ourselves … We just want better conditions. We don’t want to hurt anybody. We’ve been working for the Squatters long enough and all we get is a chunk of meat, corned beef, dry bread. We want to walk off all that.’

Early in the strike McLeod was arrested for entering a ‘native camp’ – an offence under the racist laws of the time. McLeod was bailed relatively swiftly, but strikers in the nearby area heard word only of his arrest. 200 strikers marched down the main street of Port Headland and surrounded the gaol, demanding McLeod’s release. McLeod soon appeared and the strikers dispersed. It was an act of defiance, and even more, it was a demonstration of the power of the collective action of Aboriginal workers.

Trade union solidarity

In the early stages of the strike, trade unions joined with church and women’s groups in Perth to establish a Committee for the Defence of Native Rights which held events to publicise the struggle and fundraise to support the strikers.

The Committee’s organisational efforts were supported by 19 Western Australian unions, and 7 national bodies.

Unions and unionists contributed to the flood of letters to the state Labor Government protesting McKenna and Dooley’s incarceration. ‘There can be no doubt’, wrote the state’s management Committee for the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners, ‘that the Aboriginal workers’ labour has been exploited by station owners and others, over the past years, and the organising of these workers is overdue.’

Concerted action by the Committee is considered to have played a key role in the release of Clancy McKenna and Dooley Bin Bin from their incarceration.

Sustaining the struggle

As the strike wore on, organising efforts continued and strikers found new ways to come together and to take action.

Aboriginal workers increasingly walked off their stations entirely, setting up strike camps.

While pastoralists believed that the strikers would be starved into submission sooner or later, the Aboriginal workers set about using their skills to work for a living in other ways, such as tin mining, hunting kangaroos for their skins, and pearl shelling.

This was a significant aspect of the strike. Through the years of struggle strikers would again and again challenge the right of pastoralists to claim exclusive use and control of the land.

For the strikers, access to country, as expressed through the setting up of camps and physical movement across contested land, was a pivotal aspect of their campaign.

The strike was elongated. In mid-1946 the strikers determined to hold a mass action to maintain momentum and solidarity. Strikers converged on Port Headland where a race meeting was taking place, just to be stopped by the police outside of the town.

They were ordered to stay in camp, but the strikers defied the order and marched to the nearby Two Mile Camp. The police were astounded at this act of disobedience. The police ordered the strikers to disperse, but they voted to stay put and continue their strike.

As the strike wore on it became more and more difficult to sustain the struggle. Post-war rationing of some essentials remained in place, and certain items could only be exchanged for government-issued coupons that were collected on the stations where Aboriginal workers toiled.

But now that they were on strike, Aboriginal workers had left the stations for various camps across the region, and were not receiving the coupons. Don McLeod was asked to make representations on the strikers’ behalf, but when he did so, he was removed by the police.

Hearing word and believing McLeod to have been arrested yet again, Clancy and a group of 80 strikers who were nearby marched to the police station, surrounded it, and demanded McLeod’s release.

Finding McLeod was not incarcerated, the strikers then presented a demand to receive rifle and beachcombing permits that they could use to secure their subsistence. Ultimately, ration coupons were distributed to strikers directly.

This incident was captured by the famed poet Dorothy Hewett in her poem “Clancy and Dooley and Don McLeod”. Hewett was an active member of the Communist Party and covered the strike for the party’s newspaper, the Workers Star. Hewett wrote:

The young men marched down the road like thunder,

Kicked up the dust and padded it under.

They marched into town like a whirlwind cloud:

OPEN UP THE JAIL AND LET OUT DON MCLEOD.

One of the more significant developments over the elongated period of the strike, was the creation of community-based self-supporting enterprises by the strikers. A vision for such self-determining enterprises had helped to inspire the strike.

The enterprises established by the strikers were an assertion of a form of self-determination that the racist system of control had sought to deny them. Clancy played a particularly significant role, travelling across the Pilbara in an old V8 and assisting the creation of collection points for peal shell, kangaroo skins, goat skins, and other items being collected by strikers.

Tactically, these enterprises made the strikers less reliant on a system of distribution centred on the pastoral stations.

But more than this, it was an assertion of independence, of self-determination. It was a challenge to the systems of white authority that had subjugated Aboriginal workers since colonisation.

The solidarity among the strikers in the face of economic intimidation, police harassment, and constant arrest and violence was nothing short of extraordinary. Dooley and Clancy in particular stood strong through multiple arrests and periods of imprisonment.

The end of the strike

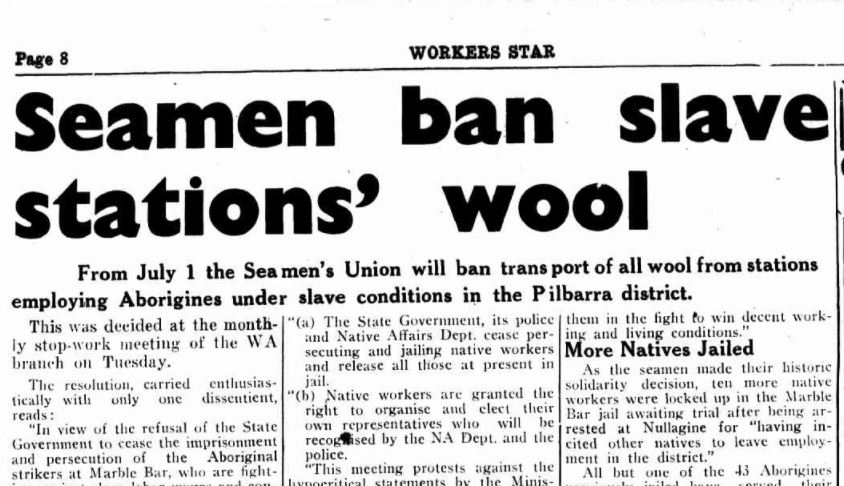

In 1949, as the shearing season approached, two pastoral stations agreed to the strikers’ demands. The Aboriginal workers reached out to the Seamen’s Union (which has a long and proud history of solidarity with Aboriginal struggles), asking its members to ban wool that was shorn on the other stations that would not concede the demanded rates.

At a mass meeting held in April 1949, the union’s members voted unanimously to protest, as was telegrammed to the government:

THE TREATMENT OF ABORIGINAL WORKERS AT PRESENT ON STRIKE IN THE MARBLE BAR AREA AGAINST THE INTOLERABLE WORKING CONDITIONS FORCED UPON THEM BY THE BIG SQUATTERS. WE DEMAND THE IMMEDIATE RELEASE OF THE 13 MEN ALREAD IMPRISONED AND THE RELEASE OF THE 30 MEN WHO ARE BEING HELD PENDING CHARGES BEING LAYED AGAINST THEM AND FAILING SAME THIS UNION WILL GIVE FULL CONSIDERATION TO THE BANNING OF ALL WOOL FROM THE STATIONS AND FARMS WHERE THE SLAVE CONDITIONS APPLY THAT BROUGHT ABOUT THE PRESENT STRIKE.

It was a powerful and effective act of solidarity.

The message was forwarded on the branch’s behalf by its secretary, Ron Hurd, a communist and a member of the International Brigades which had fought in the Spanish Civil War.

The ban was formally imposed on 28 June. The local employer group for the industry threatened to fine the Seamen for every day the wool went unloaded – a threat later acted upon.

Not all unions were supportive. There is evidence from the time that other unions actively sought to undermine the SUA’s solidarity stance, including by encouraging their members to unload the banned wool from these stations. It is important to remember that within the union movement’s history there are great tales of solidarity, but also significant times when unions failed to demonstrate solidarity with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A promise was made by the government’s representative that the wages and conditions won on the two stations would be applied as a new standard across the Pilbara. After the strikers indicated this was acceptable to them, the Seamen’s Union lifted the ban.

After the shearing season was finished, the government reneged on this promise. So the strikers had to negotiate better terms with the pastoral stations one-by-one, which elongated the struggle, but resulted in some real improvements in their wages and conditions.

What the strikers achieved

Before the strike, non-Indigenous pastoral owners refused to negotiate with Aboriginal workers. Now, as a result of the actions taken by these Aboriginal workers themselves, pastoral owners had to negotiate better wages and conditions.

Racist social myths about Aboriginal workers had been busted by their own action.

The strikers had brought a previously unthinkable amount of public scrutiny to the actions of the local police and court system towards Aboriginal peoples.

Some workers preferred not to return to the stations at all, sustaining the self-governing community enterprises that they had built throughout the strike (most notably mining).

The strike was a heroic, determined, and inspiring collective action by Aboriginal peoples seeking control over their own lives – an inherent right denied to them by the ongoing dispossession that resulted from colonisation.

It is a struggle that speaks directly to all of us today as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to take action for practical recognition, and a Voice to parliament on the issues that most directly affect their lives.

Find out how to commit to support an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament here.

By Dr. Liam Byrne, ACTU Historian

Find out more:

The Pilbara Aboriginal Strike website: https://pilbarastrike.org/

Dr. Gary Foley, “1946 Pilbara Aboriginal Stockmen’s Strike”, Tracker: http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/essays/tracker/tracker6.html

Anne Scrimgeour, On Red Earth Walking: The Pilbara Aboriginal Strike, Western Australia 1946-1949 (Monash University Publishing, 2020).