Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article does include images of deceased persons.

On 27 May, 1967, 90.77% of voters wrote YES on their ballot papers in a national referendum to change Australia’s constitution.

This remains the highest YES vote ever recorded in a referendum in Australia.

There were two specific changes being voted on.

The first was to repeal Section 127 of the constitution, which stated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples would not be counted as part of the Australian population in any census.

The second change was to Section 51 (xxxvi) of the constitution. Before the referendum this section read: “The parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to the people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.”

As a result of the referendum, the sentence “other than the aboriginal race” was deleted from this section.

The overwhelming Yes vote was welcomed at the time as a unifying statement of inclusion. It was an important part of a much longer campaign by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples against racism and for recognition and self-determination.

This year, we celebrate this significant historical event in the context of the campaign for another YES vote – this time for a Voice to Parliament for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

What was the union connection to the 1967 referendum, and what can we learn from it today?

Racist exclusion and Federation

The British colonies on the Australian continent federated into a new country on 1 January 1901.

These colonies were all based on the racist dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their land.

Colonisation also involved the development of racist and punitive systems of state authority that sought to deny Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples control over their own lives.

Australia’s Constitution emerged from this context and reflected the dominant racist ideas of dispossession.

State governments were left with free reign to pass and maintain racist and punitive laws that claimed to provide “Protection” to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples while in reality denying them even the most basic of rights.

These laws maintained dispossession. These laws denied wage equality. These laws denied access to basic rights and services. And these laws were used to steal Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families.

Senator Pat Dodson has said of the Constitution: “Australia cannot move forward while our founding document, our birth certificate, embodies our racist past.”

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organising and resistance

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a long and proud tradition of collective action and political organising to resist dispossession and to assert their fundamental right to control their own lives.

One of the most significant early political organisations was the Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) formed in New South Wales in 1924.

The AAPA was founded by activists such as Fred Maynard and Tom Lacey, both also wharfies and members of the Waterside Workers’ Federation (WWF).

The AAPA campaigned against racism and for justice. Harassment from the police and state government authorities eventually forced the organisation to disband, but it left a proud legacy of activism.

12 years later, in Melbourne, the legendary William Cooper led the foundation of the Australian Aborigines League (AAL).

Mr Cooper was a former shearer and member of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) – and he had been one of the unionists involved in the 1890s shearers’ strikes.

In the 1930s Mr. Cooper led a petitioning campaign that called upon King George V to grant “our people representation in the Federal Parliament…”

In 1937 Bill Ferguson, also a former shearer and once an organiser for the AWU, played a leading role in founding the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA).

The following year, Cooper and Ferguson helped organise the ‘Day of Mourning’ – a massive protest event to mark the 150th anniversary of the colonisation of Australia.

These political organisations had an ongoing and enduring significance to the struggle for justice.

This was also a time of collective actions by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples seeking to reclaim control over their own lives from the racist agencies of the state.

In 1936, Torres Strait Islander workers in the maritime industry took strike action over many months to protest the racist authority of the so-called government “Protector”. Their heroic action removed the “Protector” and inspired changes that allowed greater control over their own lives.

From 1946 – 1949 Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara took strike action for better pay and conditions, but also to assert their rights to determine their own destinies. The Seamen’s Union of Australia supported the strike, and in 1949 its members imposed a ban on products made on pastoral stations where Aboriginal workers were striking.

From 1950-1951 Aboriginal workers at the Berrimah reserve, just outside of Darwin, went on strike with the support of the North Australin Workers’ Union for Equal Pay. Aboriginal leaders, such as Fred Waters, were arrested and forcibly removed from Berrimah, sent into effective exile. More than 30 unions took up the cause in support of Waters and his fellow strikers.

In 1957, Aboriginal workers on Palm Island were led by the ‘Magnificent Seven’ strike leaders for five days of collective action. The strike only ended when its leaders were arrested and deported from the island at gunpoint.

These are just some examples of the many heroic actions undertaken by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers in this era that formed the backdrop to the 1967 referendum.

FCAATSI

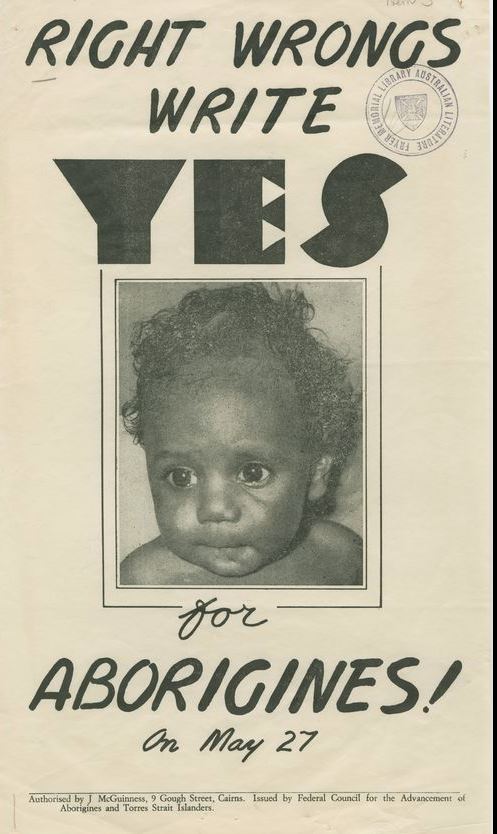

In 1958, a number of state and territory-based advocacy and activist groups came together to form a new organisation: the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement. In 1964 this was renamed the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI).

In the early days of the organisation its leadership was predominantly non-Indigenous, though by 1962 structural changes would see an Aboriginal President and a majority of Executive members being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Some of the organisations that would later form FCAATSI had run a petitioning campaign in the late 1950s around the issues that the referendum would eventually address. Between this time and 1966 at least four major petitioning drives were held to elevate the issues facing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the public consciousness.

The most influential petition campaign was organised by FCAATSI in 1962. Over 100,000 people signed a FCAATSI petition as part of this drive. In 1963, for a period of seven weeks, every sitting in the House of Representatives began with the tabling of these petitions.

FCAATSI and NTCAR influencing the union movement

In 1962, Aboriginal and union activist Joe McGinness was elected FCAATSI President – the first Indigenous president of the organisation.

McGinness was Secretary of the Cairns Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander Advancement League (CATSIAL), and an activist with the Waterside Workers’ Federation.

CATSIAL led campaigns in the local area against discrimination and for equality, often with success.

McGinness and other unionists in the organisation pushed for closer connection between FCAATSI and the union movement.

FCAATSI formed a special subcommittee on Wages and Employment, which had the specific aim of putting the ‘disgraceful position of Aboriginal workers before the ACTU.’

The other organisation of particular note in its organising at this time was the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights (NTCAR).

The NTCAR had been founded in 1961 and affiliated with FCAATSI the following year. In contrast to many other activist organisations that campaigned around Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues, the majority of its membership was Indigenous.

It was led by Davis Daniels, its first secretary and his brother Dexter Daniels, later the Aboriginal Organiser of the North Australian Workers’ Union. Brian Manning, the legendary non-Indigenous union activist, also played an integral role as part of the NTCAR.

NTCAR campaigned for wage equality, especially in the pastoral industry which was notorious for the racial discrimination shown to Aboriginal workers.

A crucial element of its activity was pushing unions such as the NAWU and AWU to actively campaign for wage equality in the industry.

The ACTU Congress of 1963

The efforts of these Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander unionists and activists, and the solidarity of their non-Indigenous supporters in the movement, had a significant effect on the policies of the Australian union movement.

The most notable demonstration of this took place at the 1963 ACTU Congress, where FCAATSI members had been pushing for the union movement to adopt a substantive policy for equality.

When delegates arrived at the Congress, they were met by eager members of the FCAATSI Equal Wages Committee distributing pamphlets and leaflets revealing the scale of exploitation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers experienced.

There was resistance to this change within the movement, but also very strong support.

Eight different unions and Trades and Labour Councils submitted motions on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy.

The motion that was adopted at the Congress read:

“Congress declares that it is the natural right of the Aboriginal people of Australia to enjoy a social and legal equality with other Australians.”

“Congress supports the current petition for a referendum to amend the Constitution.

(a) (Section 51 XXVI) to include the Aboriginal Race; and

(b) (Section 127 to include Aboriginal people in the Census.

Congress calls on all State Governments that have not done so to grant full rights to all aborigines.”

The Congress motion also declared:

“There must be an end to wage discrimination.”

This pledged the union movement to the campaign to amend the constitution that would become the 1967 referendum and to support the campaign for wage equality.

Moves towards a referendum

The ACTU’s support was significant in building momentum for a referendum. But, ultimately, it would require the government of the day agreeing to a vote for any change to take place.

Unfortunately for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists, the government of the day was the conservative Coalition led by Robert Menzies – ardently opposed to change.

Joe McGinness would later recount a FCAATSI delegation that met with Menzies to advocate for a referendum:

“We made it very clear that, as seen by us on the deputation, it was painful ironical that while a census of sheep and cattle in the country was taken and the official population number declared annually, the Aboriginal population was excluded from the exercise, and no accurate figure could be given of our numbers, which meant that animals introduced into the country had priority” over Indigenous peoples.

Under the domestic pressure generated by FCAATSI and other campaigners, and also increasingly isolated internationally due to the inequality with which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were treated, the Coalition Government (by now led by Harold Holt) eventually decided a referendum would be held on 27 May, 1967.

The Wage Equality campaign

The move towards a referendum came in the context of growing activism for wage equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, spearheaded by organisations such as FCAATSI and NTCAR who now pushed unions to take action in line with the 1963 ACTU Congress policy.

In 1965 the industrial tribunal – known as the Arbitration Commission – agreed to hear a case launched by the NAWU that would provide wage equality to Aboriginal workers in the pastoral industry.

In a sign of the racism of the time, not one Aboriginal worker spoke during the entirety of the case’s hearings. Instead, they were only allowed to observe the white litigators debate the value of their labour.

In this context, it must be said that the NAWU’s failure to call any Aboriginal workers to provide testimony during its case was a moral as well as strategic mistake.

The Commission’s hearing was indicative of the colonial attitudes of the time. The vast bulk of witnesses called were white station owners. These owners belittled the quality and character of the Aboriginal labourers upon whom their enterprises depended.

Outside of the tribunal rooms themselves, FCAATSI and union allies led a sustained campaign of public pressure, including protests, production of pamphlets, public meetings, and a mail-in letter writing campaign to the Commission.

The Victorian Trades Hall Council circulated its affiliates with requests for funds to produce leaflets on wage discrimination and individual unions provided space in their newspapers and publications for the Committee.

The Seamen’s Union took the lead in arranging for the printing of a national petition calling for all Aboriginal workers to receive ‘at least the basic wage’.

It produced an issued a special pamphlet on “The Facts on Wage Discrimination Against Aborigines” to distribute at the beginning of the Commission’s hearings. The Trades Hall Council funded the printing of 32,000 copies.

Ultimately, the Commission ruled to end wage inequality. But in a racist insult to Aboriginal workers it delayed the implementation of this equality until December 1968.

Its judgement explicitly stated that this was to provide the station owners the opportunity to replace Aboriginal workers with white labour.

Aboriginal workers were determined not to wait for equality.

Supported by Mr Daniels, workers at the Newcastle Waters cattle station went on strike on 1 May 1966 demanding equal pay.

The North Australian Workers Union banned Mr Daniels from taking further action and extending the strikes. Mr Daniels refused, took leave from the union, and went right on organising.

In June, Gurindji workers at the Wave Hill station, led by the legendary Vincent Lingiari, began a walk off that would ultimately last for nine years. Mr Daniels played an integral role supporting the struggle.

The Gurindji strike began as a protest for equal wages, but very quickly it became clear it was part of a larger struggle: the struggle for land rights.

It was led and sustained by the heroism of the Gurindji themselves. But the trade union movement played a significant role in supporting the Gurindji across these nine years.

The trade unionist Brian Manning, of the Waterside Workers Federation, volunteered on multiple occasions to drive supplies the 750 kilometres from Darwin to Wattie Creek.

Mr Daniels and fellow-activist Lupna Giari conducted a speaking tour sponsored by the Building Workers Industrial Union and Actors Equity, addressing sixty meetings in just over a month in which they explained their cause.

The Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union placed a ban on any products being produced by replacement labour at Wave Hill.

Other unions held mass meetings, raised collections to support the strikers, and pressured politicians to act.

In August of 1975, Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam symbolically poured earth from the Gurindji land into the hands of Vincent Lingiari, and presented a leasehold over part of their land.

The 1967 referendum campaign

The struggle for wage equality and against racist discrimination was a vital part of the context in which the 1967 referendum took place.

The historian of FCAATSI, Sue Taffe, described the FCAATSI Yes campaign as ‘sophisticated and wide-reaching’.

Leading Aboriginal activists such as Joe McGinness, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (known at the time as Kath Walker), and Doug Nicholls played a prominent role in the campaign, speaking on the exclusions and discrimination that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experienced across Australia.

McGinness later recalled the mass meetings of trade unions, church groups, and community organisations that were held as part of the campaign across Australia.

He and his fellow campaigners spoke of the need to extend the ‘fair go’ to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who had long been denied it – a message with deep resonance throughout the community.

When a referendum is held, the government is required to produce a pamphlet outlining both the Yes and No case on the question. In 1967 all the political parties endorsed the Yes vote, so there wasn’t a published No case.

On 27 May 1967 the vote for Yes was overwhelming.

The significance of the 1967 referendum

There are huge debates over the precise meaning and significance of the 1967 referendum.

There are many misunderstandings about just what the referendum promised, and what it delivered.

A large reason for this is that the 1967 referendum is often extracted from its broader context. Without knowing the fuller history, it is impossible to really understand what happened that year.

The 1967 referendum was of great symbolic significance and deep emotional resonance for large numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who campaigned for constitutional change.

The legendary Aboriginal activist Bill Onus, a former shearer and AWU member, who was the referendum campaign director in Victoria, said of the vote: “In this year of our Lord, nineteen hundred and sixty seven, we cannot help but wonder why it has taken the white Australians just on 200 years to recognise us as a race of people.”

The referendum itself did not provide citizenship rights to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Many of the rights associated with citizenship had been won in separate and hard-fought campaigns before the referendum, including the right to vote in 1962, and the right to equally access social services in 1966, among others.

The right to wage equality – a basic, though often neglected, citizenship right – was still being campaigned for (this remains the case today).

Many non-Indigenous supporters of the referendum seem to have believed that the vote alone would deliver greater equality immediately.

But large numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists appreciated that it was better understood as another step in a much broader and longer struggle.

This is a struggle that continues today.

This year’s referendum for a Voice to Parliament is a significant milestone in the long campaign by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for respect and recognition.

A Voice will allow Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to achieve practical recognition, and a say over the laws that will directly affect their lives.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart ends with the invitation: We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

In the referendum this year all Australians have the opportunity to vote Yes for that better future, together.

Find out more:

Joe McGinness, Son of Alyandabu: My Fight for Aboriginal Rights (University of Queensland Press, 1991)

AIATSIS, “The 1967 Referendum”, https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/1967-referendum

Deadly Story, “The 1967 Referendum), https://deadlystory.com/page/culture/history/The_1967_Referendum

Sue Taffe, Black and White Together FCAATSI: The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, 1958-1973 (University of Queensland Press, 2005)