The largest strike in pre-Federation Australia began on the 15th of August, 1890 – the Maritime Strike.

In the decades leading up to 1890 unions had grown in size and significance.

Many employers perceived this as a threat. Business interests grouped together in their own organisations and sought to push back against the growing union tide.

As the chair of the Steamship Owner’s Association put it in July 1890: ‘All the owners throughout Australia have signed a bond to stand by one another… never before has such an opportunity to test the relative strength of labour and capital arisen’.

The strike began when shipowners objected to the Mercantile Marine Officers’ Association’s affiliation with the Melbourne Trades Hall Council.

The Association represented the newly-unionised ships officers, and the last thing employers wanted was union solidarity between officers and the crew.

At the same time, the Shearers’ Union was campaigning to protect working conditions in its industry through a boycott of wool produced by non-unionists.

The Shearers asked maritime and dock workers not to handle wool that was shorn by non-union labour, merging the disputes into one.

Despite union requests, the Employers’ Union refused to negotiate, leading to an elongated and bitter dispute.

By September, 16,000 shearers were on strike.

Employers and anti-union politicians were well-organised, and more than willing to use the law to target striking workers – or even physical force.

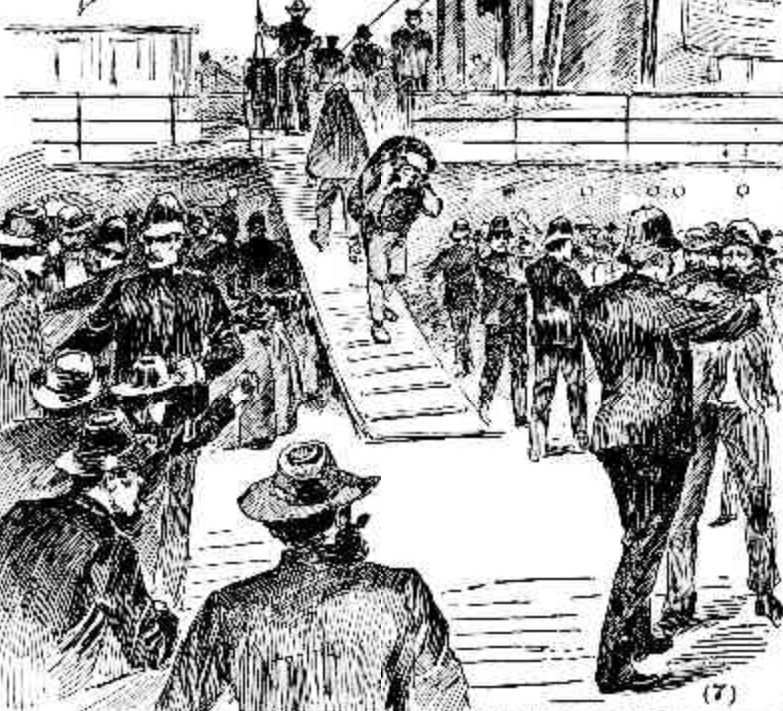

Strikers were prosecuted under long-disused provisions in the anti-union Masters and Servants Act. ‘Special constables’ were enrolled to police the strikers’ actions.

One Colonel distributed live ammunition to his troops, telling them that if clashes with striking workers took place they should ‘Fire low and lay them out’.

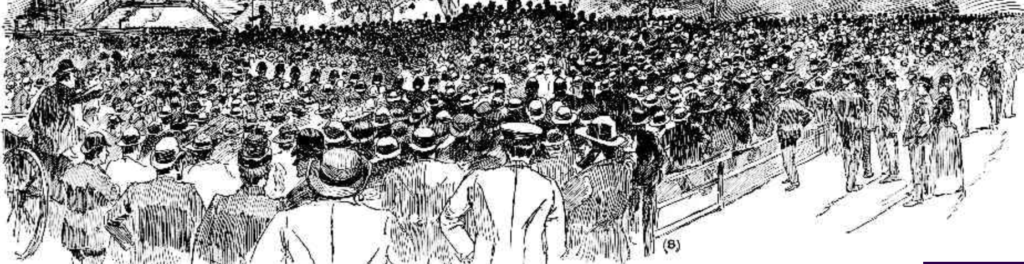

Over a two-month period, around 50,000 workers were involved in the strike, an impressive display of commitment.

But the employers were determined to crush resistance.

In October the Marine Officers’ Association withdrew its affiliation to the Trades Hall Council.

Elsewhere, the employers went on the offensive, provoking a series of bitter disputes with the shearers that would last for the next four years – the Shearers’ Strikes.

The Maritime Strike burnt deep into the soul of Australian unionism.

It demonstrated how far big employers and right-wing governments would go to attack unions.

It also made clear that it was not enough to organise in a single industry – but had to work together across the economy.

It was a spur to union involvement in politics on our own terms. It is often attributed as one of the major reasons (alongside the Shearers’ Strike of 1891) why the union movement founded the Labor Party.