By Professor Sean Scalmer, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne.

The Eight-Hours campaign is one of the great successes of the Australian labour movement. A campaign initiated by stonemasons in Sydney and Melbourne in the mid-1850s, reshaped the experience of work, drove mass mobilization, and helped to make Australia a model for workers in other lands. How did that happen?

This is not just an historical question. It is vital for unionists today to learn the true history of the struggles that went before to better understand how change can be made today. The reality of the eight-hour day movement is that it took many decades to achieve victory across industries, across these decades there were advances and reverses, and workers used and adapted a variety of tactics and strategies to win their demands. The lessons of this struggle resonate strongly today.

What are these key lessons?

First, the movement for the eight-hour day was by no means an uninterrupted forward march. On the contrary, it was marked by long stretches of apparent stillness and even reversal.

Addressing workers in 1869, the Vice-President of the National Shorter Hours League admitted “he was sorry the movement had not progressed further”. That year members of only twelve unions marched on Melbourne’s ‘Eight Hours Day’ to celebrate their victories. In 1879 there still only seventeen unions that had secured the standard, but by 1885 there were thirty-four, by 1888, forty-eight, and by 1891, sixty. Melbourne led the way, and the progress elsewhere was generally slower and more uneven. Across the continent, workers managed to leap forward only at key moments. Periods of apparent immobility were not unusual.

Second, workers waged their campaign with a great variety of methods: industrial, political, cultural.

Workers formed new unions to push for the eight-hour day. Indeed, the growing unionisation of the workforce over the later nineteenth century largely unfolded as new groups of employees sought to work only eight hours a day. Unionists understood that an enduring organisation provided them with a means to cooperate and with resources that were vital to win their claims. They constantly appealed to their co-workers to convince them of this necessity.

Established to advance the campaign, these new unions took action: proclaiming an intention to work no more than eight hours; enacting that commitment; sometimes undertaking strikes to enforce demands. Unionists also formed broader industrial and political organisations to cooperate and support one another, such as Trades Halls and Trades and Labor Councils as well as Eight Hours Associations. As they forged greater unity, so they also became more powerful.

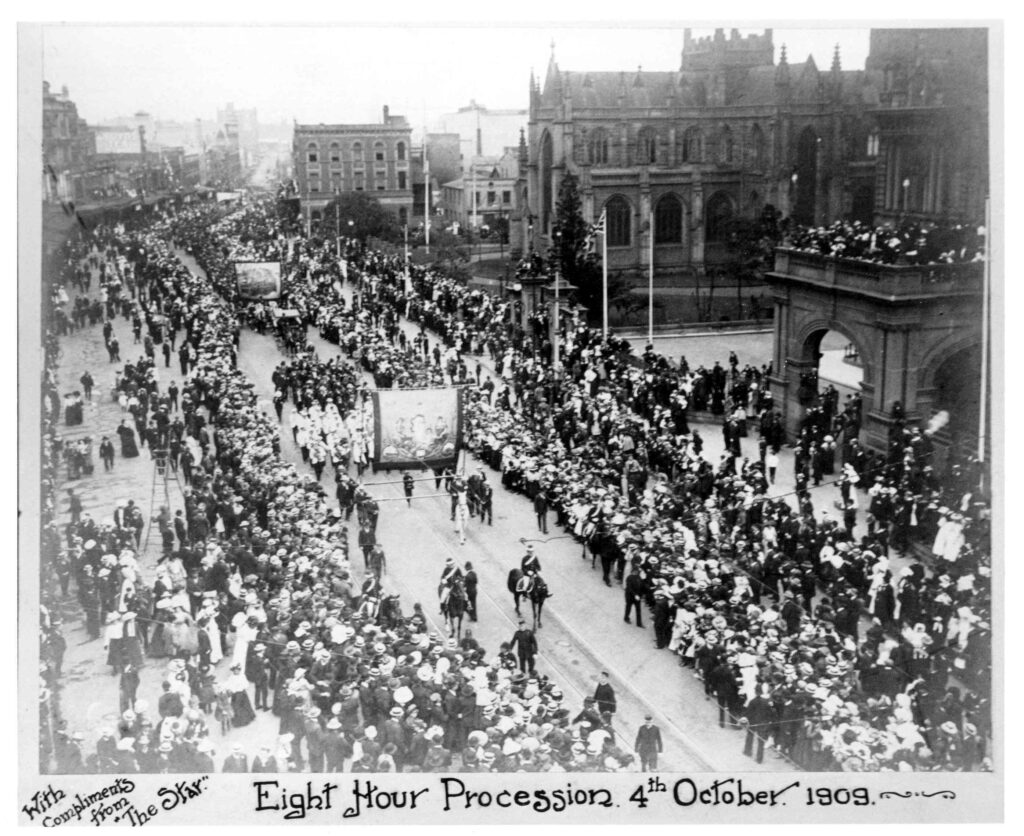

Much of this campaign went beyond strictly industrial action. Workers launched a widespread effort to convince fellow citizens that ‘eight hours’ should be a universal standard. They put their views in countless public interventions: letters to the editor, poems, songs, speeches, pamphlets, banners and essays. The ‘Eight Hour Day’ formed a central element of this cultural struggle.

By publicly celebrating their victory, unionists affirmed their deep attachment to the standard. By arresting the usual rhythms of city life, they demonstrated the power of combination and the possibility of opposing the dictation of employers. The day began with a procession of unionists but included also a carnival or fête with a sports program, musical performance, theatre, sideshow stalls, rides, banqueting, and dancing into the night. The day of celebration was therefore also a demonstration of the joys of a life beyond work.

Direct political campaigning reinforced these messages. Advocates of reduced hours held large public meetings and debates. They organised petition drives. They led deputations to government. They intervened in election campaigns and extracted promises. They demanded commissions of inquiry into industries associated with longer hours. They pressured governments to take action. In response, politicians in several colonies repeatedly presented ‘eight-hours’ bills to parliament.

This strategy was not immediately successful: there was no law passed mandating an eight-hour day across the economy. But the relentless pressure forced governments to pass legislation limiting hours for certain industries (such as mining, and shop-work) and certain workers (such as female employees and younger workers). The pressure also forced municipal and shire councils and departments of colonial governments to implement an eight-hour day for nearly all of their employees.

This was also extended in many cases to private employers contracted to deliver work for governments, such as the building of roads and rail. In this way, step-by-step, the standard was spread across occupations and areas. Each gain imposed greater political and industrial pressure on outliers. It also demonstrated that employers could certainly afford to concede workers’ claims.

The extensions were demanded by workers appealing to a principle of equality. If the stonemasons enjoyed eight hours, then why not the carpenters or bricklayers they worked alongside? If the worker who used timber and bricks toiled for only eight hours, then how could this be denied to the worker who felled the trees or made the bricks? If tradesmen, then why not labourers? If those who worked outside, then why not the employee behind the counter or at the workbench?

This was not just the cry of the exploited, for those who had achieved the demand almost invariably supported those without. Their support extended from advocacy to strategy, and from words to deeds. Boycotts isolated employers who refused to bend. Strike funds reinforced workers struggling for their rights. These efforts expressed solidarity. They were also frankly motivated by a kind of self-interest, for unionists understood that while ever some employees worked for longer than eight hours, those who enjoyed the standard would be vulnerable to reversals.

Today’s economy and society differ in countless ways from the world of colonial Australia. Much has improved and the union movement is now considerably better resourced and more diverse. Our lives also intersect with paid employment in more complicated ways. Still, the successful campaign for the eight-hour day suggests many lessons. Unionism, in its years of initial growth, emphasised the need to protect and nurture a life outside work. Its adherents promoted organisation as a prelude to more effective action. They took action that crossed from the industrial world into the political and cultural, with each element supporting the others. They understood that it was necessary to extend breakthroughs across occupations in order to secure them. And in pursuing such an extension, they demonstrated that unionism was more than a means of pursuing self-interest. It was also a means to win equality and freedom.

Professor Sean Scalmer is an historian of the labour movement. His many books include The little history of Australian unionism. He is currently researching union campaigns to reduce working hours in Australia.