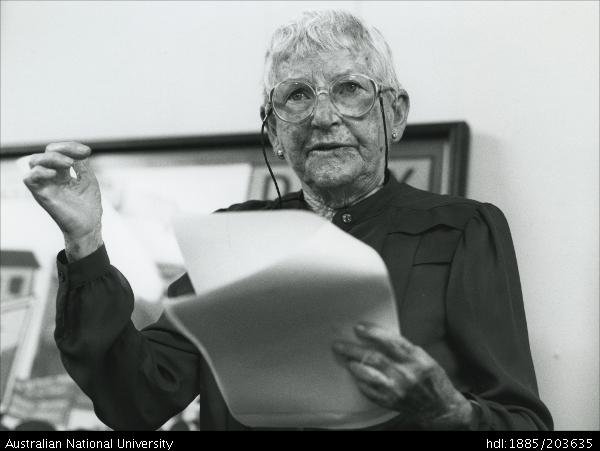

After a lifetime campaigning for equality for women workers, Edna Ryan passed away on 10 February 1997.

She left an extraordinary legacy of activism against sexism and for gender equity, including within the union movement that she proudly belonged to.

This is her remarkable story.

Who was Edna Ryan?

Edna was born in Pyrmont, in working-class Sydney, in 1904. She was one of twelve siblings.

At a young age her father was unemployed, and her mother worked to support the family.

The Australian industrial relations system was based on the concept of a “family wage”.

This concept derived from the Harvester Judgement of 1907, which created the world’s first national minimum wage. But this judgement reflected the sexism of its time, and the minimum rate of pay was calculated on what it was believed a male wage earner would need to provide for his family.

A separate minimum wage was calculated for women that presumed they would be caregivers, not breadwinners, and was set at 54% of the male minimum.

So even though Edna’s mother provided for her entire family, she earned only just over half the male wage.

At 16 years of age, Edna entered the workforce as a typist. She experienced the deeply embedded structures of sexism in the working world. She could only earn 2/3rds of the male wage and as it was presumed women would work for a few years before getting married and leaving the workforce, it was almost impossible to get promoted.

She got active in the labour movement. She complemented her formal education (which ended when she entered the workforce) with classes at the Workers’ Educational Association – she later became an organiser for the Association.

She joined the Communist Party, and was a notable activist in the 1929 Timber Workers’ strike, leading a group that was organising the families of the striking workers. But her time with the Communist Party was short: she was expelled in 1931.

She joined Labor in the 1930s, fighting hard to get the party to take sexism and women’s oppression seriously. In 1956, she was elected to the Fairfield Municipal Council, and became the first woman to serve as a Deputy Mayor in NSW in 1958. She held her council seat until her retirement in 1972.

She also worked full time as a clerk typist at an electricity authority called the Prospect County Council. She became an active member of the Municipal Employees Union, pushing its male leadership to take serious action for equal pay – instead of their regular avoidance and prevarication on the issue.

Edna was elected as President of the Local Government Officers’ branch of the Municipal Employees Union of NSW, serving from 1963-1972 when she retired – the first woman in this role.

In 1964 Edna pushed for the union to take a claim for equal pay for herself and five other women to the NSW Industrial Commission. She hoped that if they won this claim, it would set the basis for other women in the workplace to attain equal pay.

And they did win! An important, though underrecognised victory.

But the story doesn’t end there. In a subsequent renewal of the workplace agreement, the Council’s administration pushed to include gendered work classifications that would prevent other women workers there getting access to equal pay. To Edna’s outrage, the union failed to oppose this push.

These experiences helped prompt Edna to join the newly formed Women’s Electoral Lobby in 1973, bringing her long experience of activism and campaigning with her.

In 1974, Edna presented the Women’s Electoral Lobby’s submission to the National Wage Case to argue that women should receive the same minimum wage as men – a major milestone in the campaign for gender equality.

Why was the 1974 case so important?

To understand the importance of Edna’s actions in the 1974 Wages Hearing, it is necessary to start with Justice HB Higgin’s famous ruling in the Sunshine Harvester case at the Arbitration Court in 1907.

This ruling created a new basic wage. This basic/minimum wage was set at a rate based on what it was believed a male worker would need to earn to care for ‘his’ family – hence it was also known as the ‘family wage’.

The wage was set at an amount that it was believed would allow a hypothetical male wage earner to provide for ‘his’ wife and three children.

In a series of cases before the Arbitration Court Higgins formally entrenched this sentiment in the wage structure, setting the rate for women’s wages at 54% of that earned by men (except for certain industries where women and men did the same work side by side, which was rare).

This meant that a single man would receive a wage rate to support a non-existent family – whereas women, such as Edna’s mother, who were the only wage earners supporting their family earned the lesser rate due to their gender.

Working women campaigned against this injustice. It was a hard fight, and one that took many decades.

During the Second World War, women who were working in previously male-dominated industries were able to push their wages up, in some industries to 90% of the male wage. But after the war, even these gains were lost.

A 1950 increase at the Arbitration Court set the female wage rate at 75% of the male rate.

In 1969, case brought by the union movement to the Arbitration Commission resulted in “Equal pay for equal work”. This was limited to only those industries where women did the exact same type of work as men, around 18% of women workers.

In 1972, a second case brought by trade unions to the Arbitration Commission, backed by the Whitlam government, led to a ruling for ‘equal pay for work of equal value’.

This meant that if work conducted in an industry where the workforce was composed predominantly of women was considered to be similar in value to the work conducted in a male-dominated industry, the same wage would be paid.

Of course, this legal right existing, and being able to enforce it in practice were two separate things. The decision also only applied to federal awards – around 40% of the female workforce.

But the family wage, and its gendered division, still formally existed. This meant there remained a separate minimum wage for women and for men, and, of course, the minimum for women was set at a lower rate.

At the 1974 Wages hearing Edna presented pivotal evidence on behalf of the Women’s Electoral Lobby in opposition to this inequity.

This evidence, and her testimony, was integral to the Commission’s decision to end the practice of separate minimum wages (and it brought the lowest paid women’s wage up to the level of the male minimum).

This formally brought an end to the ‘family wage’ concept established in 1907.

After 1974

After her famous contribution to the 1974 Case, Edna kept up her campaign against sexism, including pushing for change within the union movement.

Edna worked tirelessly to elevate women’s voices in the movement. She established the Women’s Trade Union Commission in 1976, seeking to break down barriers between the union movement and the feminist movement.

Edna was an organiser for the first Women and Trade Unions Conference held in Sydney 1976, attended by more than 500 women unionists. This conference set the basis for the ACTU’s Women’s Charter.

She also made a significant impact as a feminist scholar, writing on the experiences of women workers and how they confronted structures of patriarchy in the world of work and the industrial relations system. Her best known works are Gentle Invaders: Australian Women in the Workforce 1788-1974 (1975) which she co-authored with Ann Conlon, and Two-thirds of a Man: Women & Arbitration in New South Wales 1902-08 (1984)

These works had a major influence on the writing of Australian history, and labour history, challenging their male-centrism and exclusion of women from the story of work and working lives.

Her contribution to activism and scholarship to advance the cause of women workers led to her being bestowed with an Honorary Doctorate by the University of Sydney in 1985.

In 1994 she spearheaded a WEL campaign about the dangers of enterprise bargaining for women workers.

She died in February 1997, aged 92.

The Edna Ryan Awards continue to honour Edna and her legacy. You can read more about these awards at their official website.

We are proud to remember Edna, and her extraordinary contribution to the long struggle for gender equity for women workers in Australia.