31 August is Equal Pay Day – a day that draws attention to the ongoing gender pay gap that exists in Australia. Australian unions have a long history of campaigning for gender equality and for the economic independence of women workers.

Fundamental to this has been the demand for Equal Pay. This is the story of some of the incredible women unionists who took action for equality!

The remarkable Louisa Dunkley and her campaign for equality in the public service

Did you know that for seven years from 1895 to 1902 women unionists in the public service campaigned for, and then won, the right to equal pay? This was one of the earliest victories for equal pay for women workers anywhere in the world.

And it was a campaign led by an incredible unionists called Louisa Dunkley.

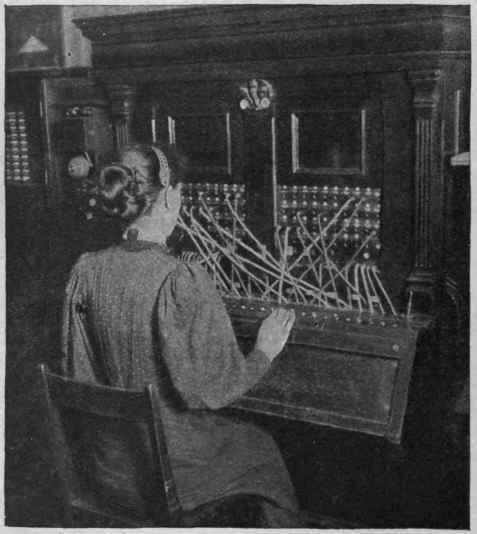

Louisa was born in Richmond in Melbourne on the 28th of May, 1866. She studied telegraphy, qualifying as an operator in 1888. While she excelled in this position, she also found she had a passion and talent for something else at this time: trade unionism!

In the 1890s, Louisa warned the male members of the Post and Telegraph Association of impending pay cuts. This Association refused to admit women members, and it failed to listen to Louisa’s warning. So what did she do? She got organised!

Louisa set up a committee of women workers to argue the case for pay equality. She won increases in pay for women workers, while the male workers who didn’t heed her warning saw their pay reduced.

When the male members of the Post and Telegraphist Association still refused to admit women members, Louisa helped to found the Victorian Women’s Post and Telegraph Association in 1900.That same year, she assisted with the formation of the Australian Commonwealth Post and Telegraph Association.

For the next two years, Louisa led union members, especially union women, in a campaign for pay equality. This included holding public meetings, lobbying politicians, writing letters, and writing articles and pamphlets.

Louisa was famous for her fiery speeches, and her advocacy for pay equality and broader gender equity was devastatingly brilliant. In 1902, as part of the Public Service Act, women working as telegraphists and postmistresses in the federal public service won equal pay.

Even after this victory she remained a dedicated union advocate.

Her employers even tried to stymie her activism by shifting her from the city to a suburban post office.

Louisa simply started cycling all the way to and from work to parliament and the various post offices around Melbourne that she regularly visited to keep up her organising.

Louisa Dunkley passed away from cancer in 1927. You might know her name if you live in the electorate of Dunkley – which is named after her.

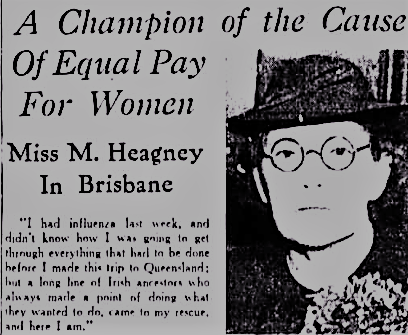

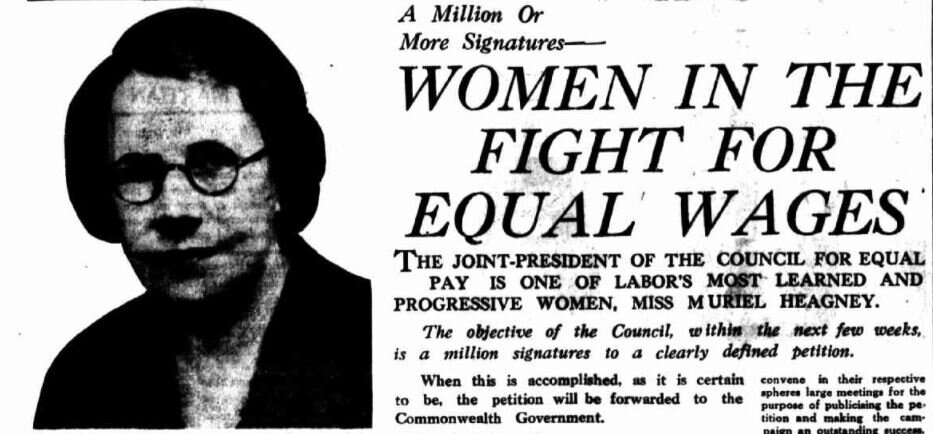

The indefatigable Muriel Heagney and her 60-year campaign for equality!

Have you heard the story of Muriel Heagney, the legendary unionists who campaigned for six decades for equal pay?

Muriel was born in 1885 in Melbourne and by the early 1910s had become a committed trade unionist. During the First World War she was the only woman clerk at the Defence Department by day, and an ardent campaigner against conscription outside working hours.

Through the 1920s and 1930s she was a prominent leader of union women and an advocate for workers’ education. This included her work for the Australian union movement in preparing submissions to the royal commissions on the basic wage in 1923 and 1927, and work for the Clothing Trades Union for its arbitration court submissions seeking equality in the basic wage for working women.

Her growing reputation as a union researcher saw her take up a brief posting with the International Labor Organization in Geneva, as well as represent the Trades Hall Council at the first British Commonwealth Labour Conference, held in London.

During the dark years of the Great Depression Heagney remained an active campaigner for working women. She helped establish the Unemployed Girls’ Relief Movement in 1930, at a time when few were paying attention to the plight of young unemployed women.

In 1935 she wrote a celebrated pamphlet titled Are Women Taking Men’s Jobs? in which she busted sexist myths of the time and prosecuted the case for equal pay for women. She wrote:

“…women consciously demand recognition of the fact that woman’s right to work rests not on the number of her dependants, nor on the fact that she does or does not compete with men, but in the absolute right of a free human being, a taxpayer and a voter, to economic independence. As such, she will not suffer dictation as to the intimate concerns of her life.”

In 1937 she was a leading light in the foundation of the Council of Action for Equal Pay – a group of women unionists who campaigned against sexism.

It wanted to change attitudes in the union movement and to take action against sexism in the workplace and broader society. This group’s activity led to the ACTU’s policy supporting equal pay, which was adopted at our 1941 Congress.

In 1941, Australia was at war. Large numbers of men were joining the military, and women were entering parts of heavy industry they hadn’t been able to before the war. But despite providing a vital service to the war effort through this work, they were not paid at the same rate as the men who had done these jobs.

Through the war years unions campaigned for increases in women’s wages – with some really important successes. Muriel was directly involved in many of these campaigns. From 1943 to 1947 she was an organiser for the Amalgamated Engineering Union – and during the Second World War many of the women who entered this industry did win wage increases.

But once the war ended, these gains were taken away. So the union campaign for equal pay continued. Muriel continued to campaign and write in favour of equal pay.

Muriel Heagney died in 1974 – one week after the Arbitration Commission delivered a ruling that ended the practice of having separate minimum rates of pay for men and women. After a lifetime of campaigning, she lived to see the legal right to equal pay become a reality.

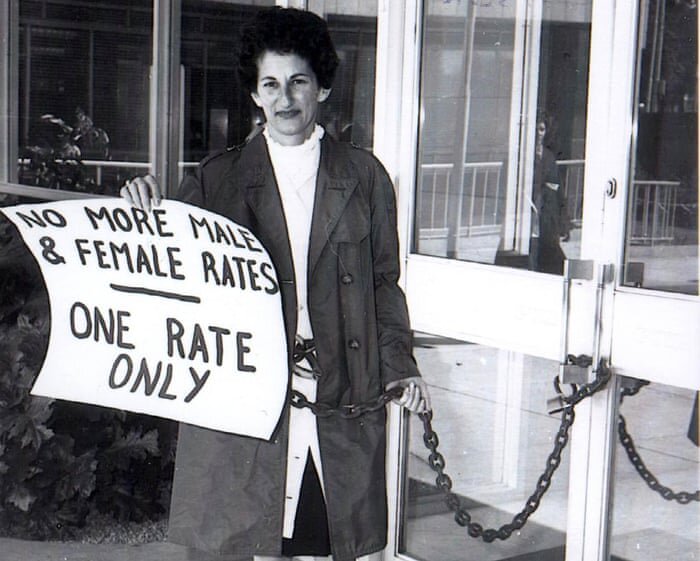

The defiant Zelda D’Aprano and her action for change

Do you know why the union activist Zelda D’Aprano chain herself to the doors of Melbourne’s Commonwealth building in October of 1969?

Zelda was born in 1928 and grew up in the Melbourne suburb of Carlton. Her mother was a migrant from Belorussia and worked in a clothing factory, while her father was a wheelwright from Ukraine. By the time she was fourteen Zelda was out of school and into the workforce, losing a series of jobs in various Melbourne factories after she kicked up a stink over unsafe working conditions. She later worked as a dental assistant and then qualified as a dental nurse, and was activist in the Hospital Employees Federation. She got politically active, joining the Communist Party of Australia.

In January 1969 she started work with the Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union, and soon gained a reputation for her courage and willingness to call out sexism, including within the union movement.

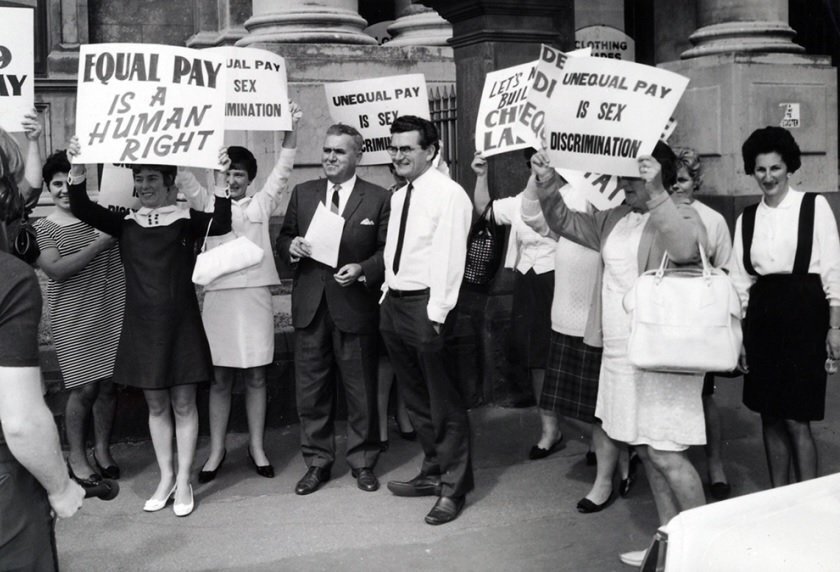

In June of that year, the Meat Industry Union was one of the trade union’s that brought a historic equal pay case to the Arbitration Commission alongside the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU). The union advocate in the case was Bob Hawke, then working for the ACTU.

The evidence Hawke presented, Zelda later recalled, was ‘profound and irrefutable’. But the hearing itself was far from favourable for the working women who were pressing a claim for equal pay. Zelda, who was present throughout the case, remembered the alienating atmosphere of the court, presided over by four male judges.

She wrote in her memoirs that ‘the women sat there day after day as if mute, while the men presented evidence for and against their worth. It was humiliating to have to sit there and not say anything about our own worth. I found the need to sit there silent almost beyond my control and was incensed with the entire set up.’

On June 19, the Commission returned its decision in favour of ‘equal pay for equal work’.

While this sounds positive – and it was certainly a step forward – many activists such as Zelda were disappointed. The decision was very limited in scope, applying only to work that men and women performed in the same manner in the same industry, affecting less than 18% of working women (predominantly in the public service). This left all those women who worked in female-dominated industries that had been systematically undervalued without equality, paid less than men who performed comparable work.

Zelda felt this disappointment keenly, and she decided that she’d had enough of silence. It was time for action.

On 21 October 1969, Zelda went to the Commonwealth Building, where a number of government offices were located, and chained herself to the entrance of the building. Other women activists marched up and down with placards chanting to draw attention to Zelda’s action, and the significance of the cause.

In an interview Zelda later explained the events of the day:

‘Well, I had to go and case the joint and look to see where the handles were on the doors. Then I was able to get the chain donated from the Painters & Dockers Union. And I had to buy the locks myself. And I had it all arranged, and I was very nervous, and the day came and we notified the press and the television stations, and I went ahead and I chained myself across the door of the Commonwealth Building in Melbourne over the injustice done to women over salaries. And I had the women there to give me moral support. And the Commonwealth Police came, and — eventually —cut me off the chains.’

This activism intended to draw attention to the ongoing cause for equal pay. The 1969 decision was not enough, all women workers should get paid equally, and the historic undervaluing of women’s work needed to be corrected.

After her heroic action Zelda was soon approached by two trade union activists in the teachers’ union, Alva Giekie and Thelma Solomon, who volunteered to take part in a similar act of defiance. It was decided that the next target for protest would be the Arbitration Commission building, as it was there that the inadequate decision on pay equity had been made. Zelda took it upon herself to examine the doors at the building and decide how much chain would be needed. This time, the Builders’ Labourers Federation donated the chain for the action. But Zelda had to buy her own locks.

On 31 October the three women chained themselves to the doors of the Arbitration Court. She recalled that:

‘There was just sufficient chain to allow the door to open slightly, and people had to bend down and crawl in sideways to enter the building. This was so undignified for the “important” people.’

In 1970 Zelda, and other women comrades, formed the Women’s Action Committee, which agitated for equal pay, and protested other forms of sexism in Australian society. In one protest they took a tram ride, and when the conductor approached them to pay for their ticket, they only paid 75% of the fare. Women and men did not receive the same wages based on their gender, they argued, so why should women be expected to pay the same amount as men?

The campaign for equal pay was far from over. Zelda and her comrades had made an important stand, ensuring the issue remained in the public spotlight, and providing vital life to the continuation of the campaign. This was strongly backed by trade unions, such as in the Metal Trades, which made direct demands on employers for equal pay for women in the industry immediately!

In 1972, the Arbitration Court heard another ACTU-backed claim for equal pay and determined that the principle should be ‘equal pay for work of equal value.’

It was an important milestone in the continuing march towards gender equity, and a testament to the trade union women, such as Zelda, who had campaigned for decades for this recognition.

Zelda remained a fighter throughout her life, passing away in 2018. She will forever be remembered by a grateful movement as a true trade union legend.

The inspiring modern unionists making history!

The 1969, 1972, and 1974 cases made equal pay a legal right – but as unionists know too well, recognition of a legal right does not make it a practical reality. Since these cases unions have campaigned to make equal pay a reality for women workers – and to make unequal pay history!

A particularly powerful modern example is the campaign led by the Australian Services Union (ASU) for equal pay for community sector workers and the historic victory it achieved on the 1st of February 2012.

In 2010, following a successful stated-based case in Queensland that led to a pay increase for community sector workers, the ASU set out to correct the injustice of unequal pay. Community sector work had been traditionally viewed as “women’s work” leading to a chronic and sexist underpayment of workers in this industry.

But the new Equal Renumeration Laws that were part of the Fair Work Act provided the opportunity to lodge a test case with Fair Work to correct this injustice. The ASU and other unions, supported by the Australian Council of Trade Unions, launched a community campaign in which community sector workers sought to win public opinion to their side.

It was courageous, creative, and extraordinarily effective.

The campaign educated the public as to the realities of the sector and put a human face on unionism. It included major rallies, coordinated dance routines, and even union flash mobs out the front of state parliaments to capture public attention. This public pressure ensured the Federal Labor Government joined the claim, and it helped to build an overwhelming case for equal pay.

These workers faced serious opposition from conservative governments in New South Wales and Victoria, as well as a number of employer groups. But this opposition could not stop the courageous union members whose determination for respect and equal treatment never wavered.

A favourable decision by the Fair Work Commission was handed down on 1 February 2012, and over 200,000 workers benefited as a result, receiving pay increases on the Award rates of between 23 to 45%.

For more than a century, unionists have been taking action to win equality. This is what unions are: organisations created by working people, for working people, that give us a voice and a way to make ourselves heard. There is a long line of union women and their supporters taking action to make a better future.

Their legacy is our inheritance. Their victories are our victories. Their struggle is our struggle. And their goal – for true equality – is our goal.

So get involved with your union. And together, let’s take action to make it happen!